More From The Store

photo courtesy Jarid Del Deo

Clyde’s brother would come to visit and the two of them would sit on some furniture I’d set out front to sell and smoke Basic cigarettes. Clyde’s brother had a successful furniture moving company and he was still almost as poor as his brother. It was bad times in that area. Me sleeping in a broken freezer didn’t improve the prospects.

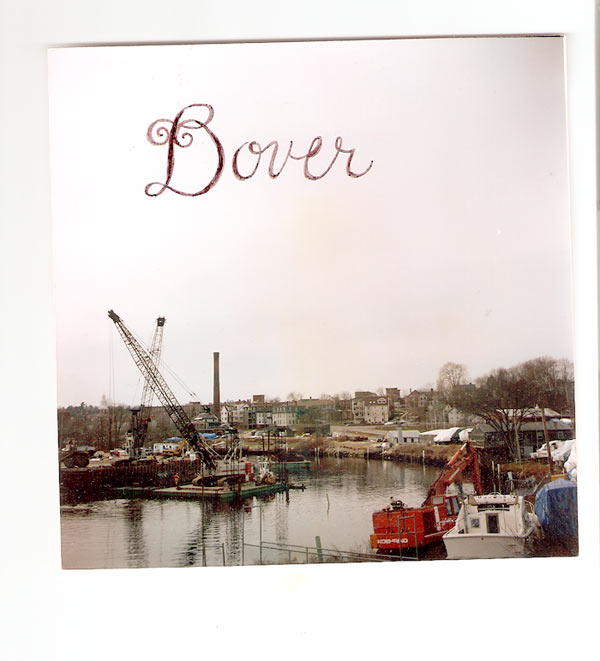

a typical scene in Dover, courtesy Dover Chamber of Commerce

I tried to keep these two brothers, both well past retirement age, at a good distance. I was trying to be somebody. It was a strange pride. I felt better than the guys upstairs, but if I was smarter, why was I living below them? Clyde loved to laugh, hold an aluminum can of beer in his hand and laugh a quick laugh with his shiny little beady eyes. “Well YES” he’d say about anything at all, or to end a sentence. Mostly to end a sentence.

“Goin’ up ta tha sto-wah. Well YES. Get me some cigretts. Well YES,” he’d announce.

Clyde’s brother went by Huff. I don’t know if that was his real name or a nickname. I didn’t engage him in conversation much. He had a speech impediment. I can picture the two of them in front of my shop. Then I picture me inside crying. How was I ever going to get anywhere in business?

Huf talked like he’d learned his words by laying hands on a speech therapists throat and mimicking the muscle movement. Still he carried himself with a sense of composure his brother’s drunken limbs couldn’t summon. I can’t say for sure, but Huff would put his hand on my shoulder and jibber jabber what I assumed was fatherly advice on how to succeed in business. It was depressing.

There seemed to be no good way to get ahead in life. A junk shop attracts a crowd along the same principle as dog shit and flies. Guys in beat up pick-ups would come by and drop hints about needing a place to fence stuff.

“I gotta lotta stuff you could sell. Can’t do it myself ’cause the Sheriff would have some questions over in Rollinsford.” Something along those lines. Of course it took a while for me to realize it. I bought Elvis’ first lp from a guy who didn’t know anything about it. They’d come in with women’s jewelry, coin collections in folders with meticulous handwriting on the sleeves of the coin cases but their own hands were hidden under engine grease and wrenching scabs. They’d ask, “This shit worth anythin’ to ya?”

I didn’t want these guys around. I didn’t even want to be there. My shop wasn’t out on Central Ave, where women ran cute little shops: one with a focus on lawn ornaments – old wooden benches, cast iron cauldrons cum planters, rusty farm implement thermometers, one lady who had neo folk wooden angels painted in faux antiqued texture and cabinets made out of old wooden single pane windows.

My shop was on a back road to Sommersworth. If I hadn’t made any money by four o’clock I threw some stuff in the bed of my truck, closed up shop and motored down to Central Ave. These women shopkeepers would stand out on the sidewalk, watching the store over their shoulder as I stood in the truck-bed holding a chair up asking, “Ten bucks for this? No? How ’bout 8?” I’d move through the pile, handing down winners, putting losers back in for someone down the road.

Daily expenses added up to 38 dollars a day. Most days it was the Central Ave ladies that got me there. If I broke 70 bucks in a day, I was doing good. I’d buy some beer and head back to the cooler.