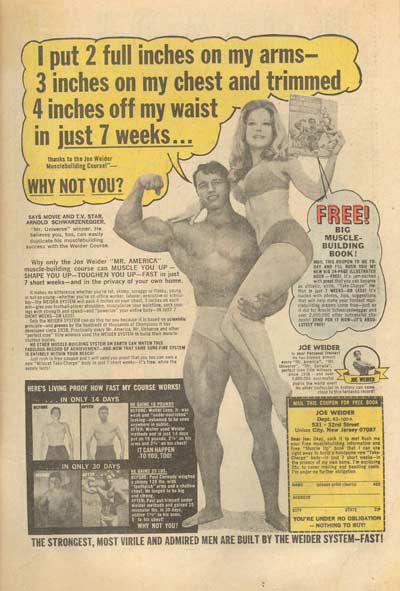

This trips me out. My governor. In a comic book advertisement.

a post card from my father’s junk shop

Does anyone know who this girl is who came to the Solstice Party with a coonskin cap on? She stepped on my toe.

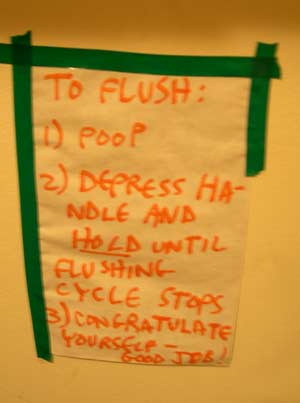

posted in Owen’s bathroom

old snowblower in the scrap metal pile of the Greenland dump

Hot dog steamer at Suds ‘N Soda

The Tequila was my christmas gift, not Dad’s.

Here’s Mom in a cool jacket that looked like it was made from a Persian rug.

Heidi wins for most spirit

Here’s the surprise video, ten days late. Sorry you can’t see much of downtown portsmouth Lyle, but it was dark out. The Portsmouth Christmas Parade, 2006!

Seen through the eyes of Ron Gallant, Greenland boy since 1974.

My Grandmother is trying to figure out what day of the week it is. I love the Holidays!

Merry Christmas Brothers And Sisters! Tomorrow or so, I mean. When is it? Coming up fast I’m sure.

This time of year always makes me sentimental for drinking alcohol. So I’ve been reminiscing quite a bit this week. Egg Nog and Spiced Rum, 30 packs of Bud bottles on sale at the Mobil-Mart, drinking in the car in the driveway so my parents don’t find out…ahh, Christmas!!

The Stockpot overlooks salt piles and scrap iron. Before they banned smoking inside, I knew who to expect in there. Today Marsha was the only one I recognized, and we had walked in together. It was slow and we got a table at one of the three windows so we could watch the action of the riverfront. A yellow loader moved piles of road salt around the dock. The river’s surface was pocky like a bad case of acne and yellow bouys bobbed up like boils ready to burst. Boy. Boy oh boy. It was beautiful. The bridge to Maine was a single span and a small pleasure boat ripped a wedge as it headed up to the bay.

The server set two coasters down, then a pint glass of local brew on each of the coasters. Marsha was talking about her dead grandmother.

“What is it called, when you have those squares of plastic mesh and people weave pictures in them? Anyway, she had one of those in the shape of a hand, and it said ‘BINGO’ here on the palm. It was on a stick and she would hold it up when she won.”

Her Grandmother loved bingo.

“I wanted to bring it to the wake but my father was worried someone would steal it. Who would steal a bingo hand at a wake? We should have thrown it in her grave before they buried her.”

She picked up her beer, the foam was just a thin scum across the top now. I had taken a sip already, and then a good drink.

“BINGO!” I shouted, pretending to throw down the bingo hand.

A face of the salt pile collapsed and I mentioned it.

“That’s because that tractor is digging into the pile,” Marsha said. “The funeral director was so weird.”

“Why?”

“Making inappropriate comments. ‘That was a pretty big rock on your Grandma’s hand.’ (she was loaded) ‘I thought I was gonna have to cut her finger off below the knuckle!’ Can you believe it? Or, ‘I thought I was gonna hafta inject her lips with solution they were so dried up, but then they turned out all right.’ Who would say that?”

People continued to drive over the bridge, just the shine of sun on metal roofs flashing in the distance.

“We all sat with our backs to the casket and talked to other people, no one stood up and said anything about her, except Kai, who had to read a prepared speech from the Church about unbaptised people going to hell, like Kai and I. My Grandmother gave a lot of money to the church and the Priest kept talking about how devout she was. She was never nice to us.”

A lot of thoughts went through my head, about my own grandmother especially. She’s 86 years old and will be gone from this world soon. She’s very nice to me and I will miss her, but we don’t talk to much. She tells the same stories from her childhood over and over.

“The Pickering Farm we used to call it. My father had it torn down during the Depression because he was worried tramps – that’s what they called them, men who walked along the tracks looking for a handout or a place to sleep. They’d knock at the door and my father would always say, ‘There’s a pile of wood that needs chopping if you want something to eat’ and he’d feed them supper if they wanted to work. But he was worried someone would burn it down so he had it torn down.”

My grandmother sits in her chair facing the television, which I ask her to turn off because I’ll try and listen to it and her at the same time, and end up tuning her out. I sit beside the television facing her. She looks at me and tells me something new this time.

“My father had it taken apart, all the windows and doors and the fireplace mantel he had stored, because it was a very old house. From the 1700′s. I can remember as kids we would play inside it. There was a secret set of stairs behind the chimney that led to a hiding spot. A lot of old houses had them, if the Indians attacked they could hide.”

I tried to imagine that house standing where fiddlehead ferns grew now. The Indian shutters that closed from inside the house to keep them out. I couldn’t picture Indians on this land. Indians seemed like something out West, a product of cowboys. To her perhaps it was like the World War Two cement bunkers along the Atlantic are to me. Run down crumbling moments from a time I never knew, but heard stories about. Those WWII stories had replaced the Indian stories my Grandmother heard and it was impossible for me to imagine what she was talking about.

Marsha and I finished our beers and while she went to the restroom I paid the tab. When she came back we walked out into the cold air, my nose dripping as it readjusted to a new temperature. I hugged her goodbye and went to my car, she to hers. I drove around town for a while, going to find the new library I heard they had built.

The streets of Portsmouth were changing, some slowly, imperceptibly, a dying limb removed, a new lilac planted. Others, like where the new library was, I could still imagine where buildings once stood that were now gone. I drove down streets that should have triggered thousands of memories, but they didn’t come up. 15 years had passed since I had walked the sidewalks, doing things I thought I’d always remember. Instead, I had a vague sense we had skateboarded in that driveway, and used to cut throught that yard, but none of things that made me laugh back then could I remember. My memories had gone the way of my grandmothers. I could remember where buildings once stood. I could remember I once played, and I could remember that that play felt really good. I could feel an absence, because I didn’t play like that any more. But those memories were so thin. A feeling attached to houses, or corner stores. Halls in a high school. Nothing specific.

Perhaps someday I’ll be old and sitting in front of television because there is so little to remember. It will be important for new things to happen, and my legs will be unsteady, my ankles weak, my knuckles swollen and my fingers rigid. There is no way to go out and play in the woods. I won’t sit and remember the good times. There will be my mind, thinking about changing the channel, or moving the cat who is napping in my lap.

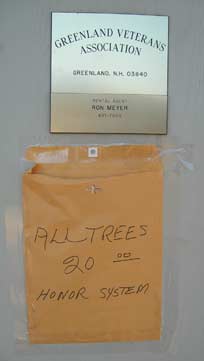

The Vet’s Hall is right across from Sud’s ‘N Soda (Jimmy McKenzie’s place) at the first traffic light the board of trustees voted to install. I was 9 years old.

“Why do they make us stop, Ma?” I asked.

“Lot’sah people got smacked up and died heeyah.”

It would’ve helped if I’d learned right then that there’s no stopping getting punished for other people’s mistakes. Unfortunately I tried to be above the law for a lot more years after they put that traffic light in.

That Vet’s Hall though. A little one room brick building, the old schoolhouse my grandfather went to. The Vet’s had imported Christmas trees leaning up against wooden forms out in the parking lot, starting at 15 bucks apiece. Wind had come through and knocked a few over, but no one was too concerned. Christmas was five days away, the Vet’s had cleared $9,000 profit on the five hundred trees trucked in, and Charlie, who was manning the lot, was keeping warm inside sipping on brandy he’d brought from home.

When my Dad and I showed up to collect the hams for the food bank Charlie was just coming out of the toilet and he right away offered us a drink. He had the combination to the lock on the liquor cabinet and was happy to spread the reason for the season around.

I had a Seagram’s Seven and Ginger Ale. The clear plastic cup, the ice cubes in the plastic bag torn open and tossed in the freezer, the American flag draped from a pole above me. I was in America, the country these men fought and died for. When your Grandfather died to free you, it’s easy to laugh at his stupidity for going to war. When your peers fight for a less clear reason, you think a little more about your grandfather, and freedom. Still, America is standing. Christmas tree lots around this country are staffed by guys drinking on the job, just getting out of the house, making a few extra bucks, keeping busy.

They sell wreaths too.

I’m in my father’s den. Behind me are stacks of coins, the small squares of white cardstock with cellphane circles cut in them, circles of different sizes corresponding roughly to the sizes of american coinage: pennies, nickels quarters, half dollars. One coin per square, stapled shut with four staples, stacked in leaning tilting Jenga piles. I’m home for Christmas, on the computer while the rest of the family sleeps.

Heidi, my sister, is staying with my parents too. She just moved back from her teaching job at a Christian school in Tennessee. She has the guest room. My grandmother lives downstairs, in the bottom part of the split level ranch house my parents own. My parents have a large master bedroom with a antechamber, a foyer, a waiting room area when you first walk in. They set up a twin bed for me there. The three cats, Fritz, Pounce and Widget sleep in my parents room as well. (Yes, it’s weird to me too. I’d sleep in the den but there is only a little trail of carpet visible between boxes, file cabinets and cardboard tables set up to hold his collection)

It was 48 degrees tonight, according to the First National Bank thermometer on Route 33. “Pretty warm for ten at night in mid-December,” my father remarked. He’s talking about New Hampshire. My sister and mother were baking gingerbread cookies and the house smelled like warm brown sugar. The two black cats, Widget and Pounce, are terrified of motion, and ran and hid when I arrived. My mother’s daily prayer book was on the kitchen table, Dad and I sat down and played a game of cribbage. I drank egg nogg and spiced rum. I lost to my father, and he went to bed. I lost to my sister, and she went to bed. Now I’m going to bed.

Pacific Gas and Electric street cover. The Bay Area’s energy provider. Does this make you homesick for San Francisco?

Or does this do it for you?

Boy blond? “It’s a brown hair color that if a girl had it, she would either dye it lighter or darker, cuz it’s kinda bland.” She had light blond curly hair, the color of hay. I tried to see if it was bleached. It was too dark in the bar to see roots, but I believed her. I was boy blond.

Hitting bottom ain’t so bad. At least you have a firm place to stand. You’ve come to a conclusion, you gave everything you had. You didn’t quit till you crossed the finish line. At that point you stop drinking. There is no challenge left, you know you rode the bull till he stomped your spinal cord too hard to ever let you ride again. You can still wear the chaps, you earned ‘em cowboy. No shame there.

I’m back at work at the junk mail factory with my old pallet jack operating friend Sean. We had a 16 foot box truck full of circulars to deliver to the downtown distributer and with this holiday traffic being so bad, Sean was slowly reviewing his evening of cable television from the night before.

“The wife and I were in bed by ten to catch Intervention. That’s the one where they showcase a couple of drunks and a druggie and the families send them away to get sober.”

We were at a dead stand still right at the Cesar Chavez exit on the 101. The truck was rumbling at idle beneath us, we sat right on top of the 6 liter diesel.

“You ever hit bottom?” I asked Sean.

“Oh yeah, couple times. I remember waking up at the Golden Gate Bridge toll plaza, off to the side where the maintenance crews park their vehicles. All the doors of my Subaru wagon were open, my feet were sticking out the hatchback. It was almost noon and I was in my underwear. I had no idea where I’d come from. I still have no idea. That whole night is lost to me. I wonder why I decided not to cross that bridge…”

Sean looked wistfully out the large windshield towards Potrero Hill, wondering how his life may have changed had he made it to Marin County that night.

“Then there was that time in Hawaii, when I was sailing, where I passed out in a park and woke up to a homeless guy shaking me, violently, just shakin’ the shit out of me. He had me by the chest, holding my t-shirt balled up in his fists and he was knocking me backwards into the tree I had propped myself up on.”

Sean crept the vehicle forward in the slow moving traffic, looking down at the passengers in the vehicles below us. “Pretty one there” he mumbled, then went on.

“I remember opening my eyes and seeing his filthy beard, and he was shouting. But I didn’t want to wake up. So I shut my eyes and went back to sleep. It didn’t matter. That there was probably the first sign I had a bit of a drinking problem. But the Navy does that to you.”

Hitting bottom ain’t so bad. It’s a firm place to stand.

Lyle is worried about sugar in boogers and angry I haven’t written. Folks, it’s season time. The special season. A magical time of the year with special seasoning. I’m busy, my camera broke, my cell phone was thrown to the floor in a final fit of rage against the machine and Sean Macdonald and I fried my truck’s alternator jump starting it friday night. I’m having an expensive week.

More importantly, and more demanding of my time, is the new dildo washing service I’m trying to start up. You know how sex crazed these gay lesbian bi transgendered San Franciscans are, don’t you? Have you ever been here? They give out condoms at church in this city. They pass around two offering plates, one you put money in, the other you take a condom out.

My business acumen stresses recognizing unmet needs specific to a given community. San Francisco? Dildo washing. The first commercial venture specializing in sterilizing the many types of plastic involved in sex toy construction. I’ve been at industrial supply warehouses asking a lot of questions and it looks like the Hobart food service company sells a superior product. Temperatures up to 250 degrees, easy lift doors, and capacity to handle gay pride parade numbers. Check this beauty out!

Powered by WordPress | Managed by Whole Boar